Bad Introduction

Collections of newer and older comics. A very short animated film. A round of Roulette. More great classic fiction.

Pair of Aces

A Sunday strip on page 55 of Jam-Packed FoxTrot: Peter and Roger are playing poker at the kitchen table. Roger checks his first two cards and sees that he’s holding the aces of hearts and diamonds. The punchline panel has his eyes dangling by their bloody optic nerves out of two gaping-black empty sockets. An arrestingly bizarre and uncharacteristically grotesque FoxTrot joke.

The library demanded Jam-Packed FoxTrot back because someone else wanted it so I will have to wait to finish it. I got the next Fantagraphics Popeye volume, E.C. Segar’s Popeye: “Well, Blow Me Down!” Here’s the problem, though: I started reading the Introduction by some critic named Donald Phelps and it is quite literally the worst scholarly introduction to a book I’ve ever read.

Here is the second sentence from Phelps’s intro:

In the manner of the one-night-stand theaters after which they were patterned — with who knows what rich reinforcement from Segar’s memories of his boyhood in Chester, IL where he worked at the opera house — they seemed to have acquired their background on-the-run, from the leavings of previous troupes and houses — the Oyls’ meagerly furnished little house, with the tiny end-tables draped in floor-length, black-bordered cloth; a Segar Furnishings touch, which he may have appropriated from the comparable décor of his revered neighbor in the New York Journal, George (Krazy Kat) Herriman; the barrenness of the open countryside, which is obviously present only to usher them toward their adventures; all these set off the ever-more-foxy, willful, casually cruel, explosively gallant presences; which never have any apology to offer for their seediness, nor will yield an inch of their right to parade their funny, barnstorming wares.

This doesn’t go quite far enough to make Phelps the Judith Butler of classic comics introductions; Phelps is indeed actually meaning something substantive rather than simply typing fancifully meaningless words, particularly if one has read any of Segar’s Popeye comics and so stands any chance whatsoever of getting a grip on what Phelps is trying to describe.

But holy shit, man, someone at some point in Phelps’s education got this guy into semicolons and em dashes and gave him the idea that as long as he kept sticking them in between clauses he could put as many facts, allusions, opinions and references as he wanted into any single sentence that just runs on and on and on and on and on. I’m reading an edition of Don Quixote that is nine hundred and forty pages long, not counting the Translator’s Note to the Reader or Introduction, and in the six hundred and forty-eight of those pages I have read I have not once come close to being as bored and demoralized as I am by the above-quoted Phelps atrocity.

Here are the first four sentences of the “Introduction: Don Quixote, Sancho Panza, and Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra” by the eminent critic and professor Harold Bloom:

What is the true object of Don Quixote’s quest? I find that unanswerable. What are Hamlet’s authentic motives? We are not permitted to know.

Bloom should have written the Popeye introduction as well. He was a bright guy and a far better writer than Phelps. I don’t give a shit how much he knew about Popeye.

Dream of Dreams

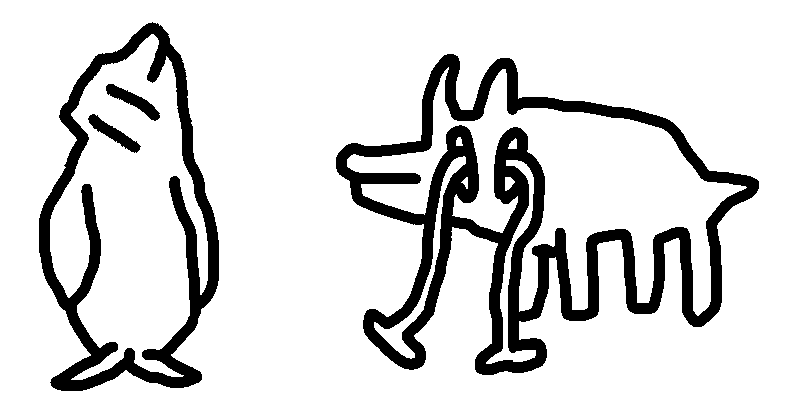

The only (very short) movie I’ve seen recently is a lovely and self-contained ninety-second piece of animation called Dream by a Disney-trained animator and art teacher named Aaron Blaise. A friend who studies drawing and composition with Blaise brought Dream to my attention and explained that it was made by Blaise entirely on his own and was released a few months ago as a promotion for Procreate’s new animation product “Procreate Dreams.” It’s a wordless story about a penguin who wishes it could fly.

While it is a great piece of modern micro-filmmaking unto itself, this was mainly a product demo intended to show what a brilliant animator could do with this fancy new animation software. The results are astonishing as a study in craft and rewarding as a piece of straightforward, all-ages-friendly entertainment. Dream is a concise, charming and beautiful piece of one-man animation that looks pretty much almost as good as some of the finest Disney features of the Nineties, such as Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King, on which Blaise worked .

Roulette

Bringing In the New Year by Grace Lin, read in 2021. I read this one late in 2021 for a New Year’s-themed entry, my first of 2022.

The Strange Library by Haruki Marukami, translated by Ted Goossen and designed by Chip Kidd, read in 2019. I read this on a train from Seattle to Portland when my then-girlfriend and I were on our way for an overnight stay to see a live podcast-recording by the Frosty Fellas of The Worst Idea of All Time. (I was sitting in the front row, so if you find the episode entitled “A Wake for The Knife” and skip to minute 31 and second 15 you will hear an extended bout of my boisterous American laugh.)

Murakami’s story is a grim, eerie and unsettling novella of a descent into a dungeon-like underworld beneath a public library. But the book as presented has a bravura conceptual twist: it’s a collaboration with the phenomenally great designer and layout artist Chip Kidd and uses all sorts of physical design flourishes that transcend the mere transmission of narrative information. You have to unfold an elaborate set of flaps in different directions to make it through the text and, if I remember right, Murakami and Kidd also employ type of varied sizes and colors to enliven and redirect the reading experience. It’s a peculiar and wonderful piece of work that transcends the boundaries of literature and design by letting them commingle into some unnamed creative genre about which I have deeply mixed feelings. As inspired as I am by whatever The Strange Library represents, I’m intimidated by all the inconceivably infinite directions into which this novel medium could ricochet if we were to unleash it. But it’s too interesting not to find out, so I think we should hope for more boutique publishing experiments of this kind.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, read in 2020. This classic of American literature has probably never been mentioned in One Could Argue before because it was the last work of fiction I read before I launched this newsletter. It’s very good, though I’m by no means devoted to it like some bibliophiles. I think it’s basically about the very American promise and tragedy of believing you can turnstile-jump the constraints of class origin and remake yourself as anything you want. I wonder if Fitzgerald were alive today whether he would have more or less optimism about that proposition.

Don Quixote: Hallucinations and Confrontations

As noted above, Don Quixote is still entertaining the shit out of me. In Chapter XXIII, yet another chapter that the metafictional “translator” found “so impossible and extraordinary that this adventure has been considered apocryphal,” Don Quixote is compelled to go spelunking into the depths of a Cave of Montesinos from which he comes back telling of vivid delusions of a magical Arcady-type environment where he interfaced with characters from classical European literature like Montesinos and Durandarte. This sequence has a Gulliver’s Travels tinge to it and brings me back to my hypothesis that Swift was influenced by Cervantes.

A noteworthy episode in Chapter XXVIII has the bitterest disagreement yet between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. It happens after D.Q. gets them into some hostile trouble and then hastens to cover his own ass after his lunacy (combined with Sancho’s poor but well-intended manners) gets Sancho knocked out cold with a pole. After they are reunited and Sancho comes around he quite understandably gives D.Q. some very straightforward feedback about what an asshole he’s being and I have to say that I was entirely with him; this is by the far the most I have disliked D.Q. up until this point. That’s the genius of Cervantes on display: D.Q., for all of his bluster about knight errantry and his demonstrations of bravery when he is for example riding into battle against a flock of sheep, should have been expected to stand his ground and defend his loyal squire, or at least to grab Sancho’s unconscious body before succumbing to his more unflatteringly cowardly instincts and riding away.

Notwithstanding his deep insanity, D.Q. is also articulate and manipulative enough to rhetorically convince a reawakened and initially pissed-off Sancho to subsequently well up with tears of codependency. There is so much I like and admire about D.Q., but I’m realizing just how effectively his most salient flaw, that of his being crazy sometimes to the point of incurring bodily harm to himself and others, can often outflank his many good traits.

I like Sancho telling him off; makes me less heartbroken on Sancho’s behalf and generates some fine comic silliness. To some extent the interplay between these two does remind me quite a lot of the nearly friendship-destroying bickering of Popeye and Castor about which I wrote back in June. A newspaper comic-strip version of Don Quixote drawn in Segar’s line would have been something to marvel at for years; I wonder if anyone anywhere has ever attempted anything like it.