Beat and Shovel

I watch a short documentary. I read books of poetry in a coffee shop, a museum and a bookshop. I write a poem. I walk in the rain.

Yesterday I watched a short “impressionistic documentary” from 2014 directed by Melanie La Rosa called The Poetry Deal: A Portrait of Diane di Prima. I was unfamiliar with the feminist Beat poet di Prima; it was cool to learn some new things about literary history and San Francisco history, even though I’ve never been much drawn to the Beats. (Except Bukowski, if he counts. I don’t like his poetry but I dig his Chinaski novels.)

I ventured out by foot and bus, on a day so wet and windy that a public advisory had strongly suggested to indulge in no non-essential travel of any kind, to find a di Prima book at the main branch of the public library. Some days before, while at the North Beach library branch for volunteering, I had perused their special Beat section and had withdrawn books by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Janine Pommy Vega. I took all three books to North Beach’s Caffe Trieste, the espresso hangout orbited by Beat fixtures for decades.

I ordered an espresso and read Haiku, a collection of di Prima’s poems with illustrations by one George Herms. The illustrations were weird, crude, bold woodblock prints that I liked well enough. The seasonally-organized haikus were more quiet, unassuming and inoffensive than I had perhaps come to expect from di Prima’s admirably brash and outspoken documentary persona.

I hardly ever write poetry; the last time I tried was years ago when I wrote a mediocre sonnet about the movie Die Hard, just because I had never attempted a sonnet before. I decided to write a poem in Caffe Trieste, be like a Beat for a few minutes.

I used a formal constraint called a “Golden Shovel,” devised by a poet named Terrance Hayes, which I learned of from the work of X.P. Callahan. I decided to use a random number generator to pick one of the eight poems from Vega’s book and then to randomly pick a line from that poem to use as the basis for my Golden Shovel.

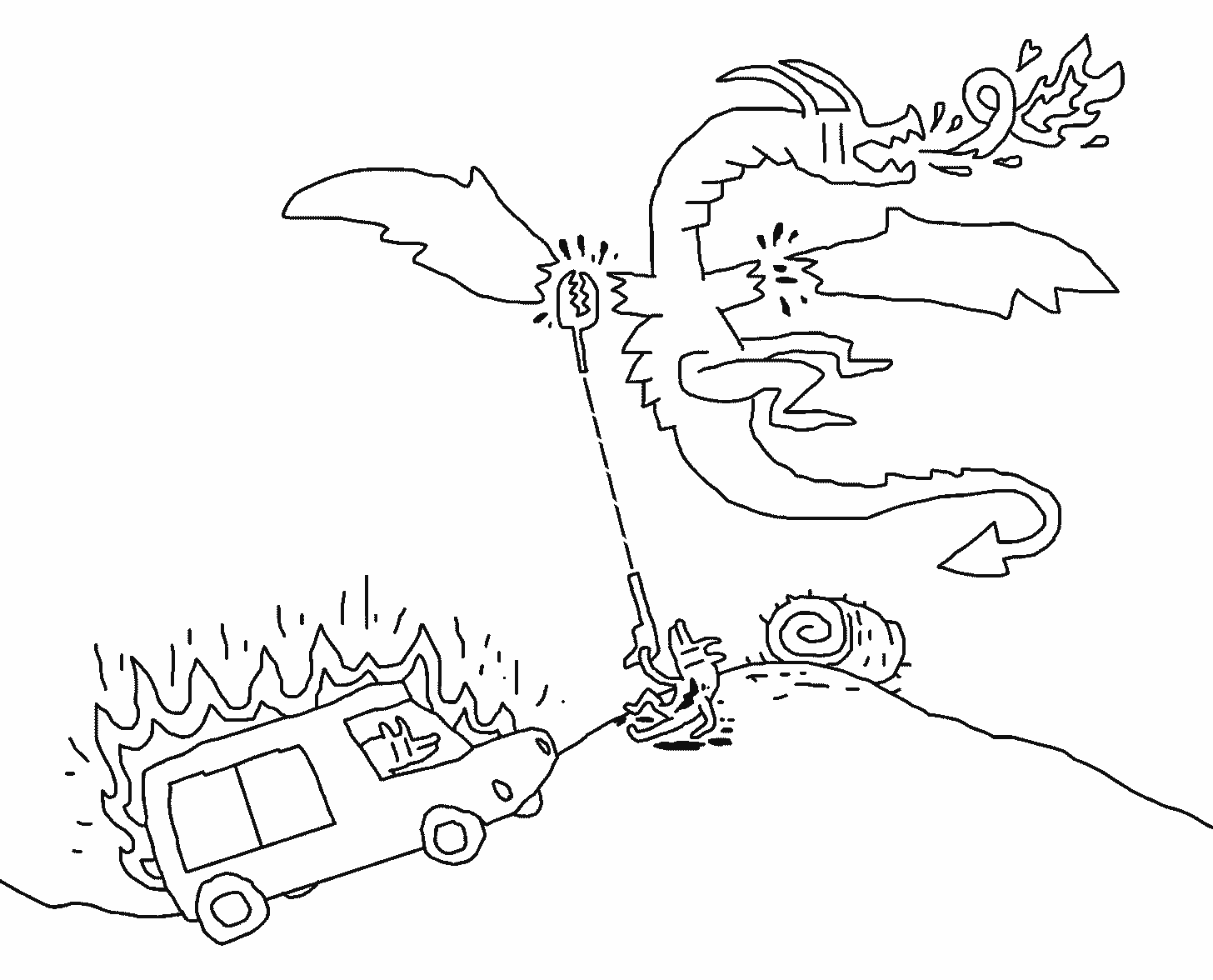

Unfortunately the line the random number generator turned up had only one word in it, “wholly.” Not enough to Shovel on. So I just picked a line I liked from Vega’s poem “Beltane” and scratched out my poem from there. It ain’t Paradise Lost, but now no one can ever again say that I have never written a poem inside of Caffe Trieste, which frankly I’m getting tired of hearing from people. Without sharing the poem itself, here is an illustrated interpretation. Please make a woodblock print out of it.

I went back out in the rain and around the corner to The Beat Museum, one of the few San Francisco museums I’d never before taken the trouble to visit and to which I had obtained one of those handy free tickets through the library system. (The guy working the counter didn’t even really care if I had a ticket at all, waving me through with a “You’re all good, man.”)

Inside the Museum I stood before a photo portrait of Ferlinghetti and read his book Back Roads to Far Places, a “single long poem of intimately linked verses” which Ferlinghetti printed in his own handwriting for the book, writing in the first line “Let my Japanese pen tell its story.” This was the first Ferlinghetti book I’ve ever read, primarily knowing him previously from representing the least interesting part of a favored movie, the Scorsese San Francisco concert documentary The Last Waltz in which he interrupts the cavalcade of remarkable musical performances to recite a boring poem.

I hung around the Museum for a little while and then went across the street and down the block to City Lights, the bookshop and publishing house established by Ferlinghetti in 1953. It’s a pretty amazing legacy; even though his poetry doesn’t blow my skirt up, the guy accomplished a lot in life, including this wonderful shop which is a crown jewel of one of my favorite SF neighborhoods. I’ve been there in the past but this time I noticed, having just read Back Roads to Far Places less than an hour before, how many of the signs hanging up around the exterior and interior were clearly scrawled in Ferlinghetti’s handwriting. Some of them exhort visitors to “HAVE A SEAT + READ A BOOK,” which I did, taking the first open chair I spotted in the subterranean section of the shop and propitiously finding that I had situated myself right across from a book by my old undergraduate writing teacher Samuel R. Delany.

I sat and read Vega’s book Skywriting, which was published by City Lights in 1988 and is said to be Number 5 in “The Accordion Series.” (Like di Prima, Vega is a writer I had never heard of before yesterday.) Vega’s eight Beat poems were no more or less interesting to me than the di Prima and Ferlinghetti Beat poems I had read, and I think we can safely conclude that there’s a reason I never got heavily into this particular literary scene. But as with the forms of both of the other books more than with their poetic content, I was enthused and excited about Vega’s: this modest cycle of poems, several of which have to do with Vega traveling in Ireland and taking an ayahuasca ritual in Peru (decades before it became a rite of passage for other, wealthier denizens of San Francisco), is contained within a single foldout accordion page that is pasted against a hand-crafted stab-bound interior with a brush-stroke cover designed by Ferlinghetti. On this rainiest of days, these Beats made me feel sunnier than I have in months about the fun and value of living an abnormal lifestyle and making experimental creative shit.

From there I walked in the insistent downpour back to the North Beach library, preparing to do some prearranged volunteer tutoring at the cafe across the street. But my learner was understandably reticent to go out in that climate after a long day at work, so we decided to wait for a different day. So I walked in the rain some more, up and down some lovely hills on ghostly streets to Van Ness Avenue to get a southbound bus, becoming soaked to the bone and fretting the vintage library books in my waterproof bag. On the bus I was drenched through, but that bag earned its stripes. The books were safe and my heart was full.