Good Scraps

Considering one particularly masterful color Sunday strip by E.C. Segar.

Go to the library and get your hands on the Fantagraphics book collection E.C. Segar’s Popeye: “I Yam What I Yam!”. Flip to pages 154 and 155 and scope the color Sunday strips from August 10 and August 17, 1930.

Here are two sterling and masterfully-executed exhibits modeling one of the niftiest tricks when cartooning on a page-scaled grid. Both are twelve-paneled strips divided into four tiers of three rectangular panels each. Both are examples of how when working in this format a truly great cartoonist, quite possibly without having intentionally planned to do so, will arrange the contents of the panels, grids, tiers and entire page so that the strip can be read in any and all of these ways.

Take the strip from August 10, 1930. Not going to print a photograph of it in this newsletter because with respect to titans of the medium like Segar the only cartoons I put in this column are my own. Track the strip down on your own to check my analysis.

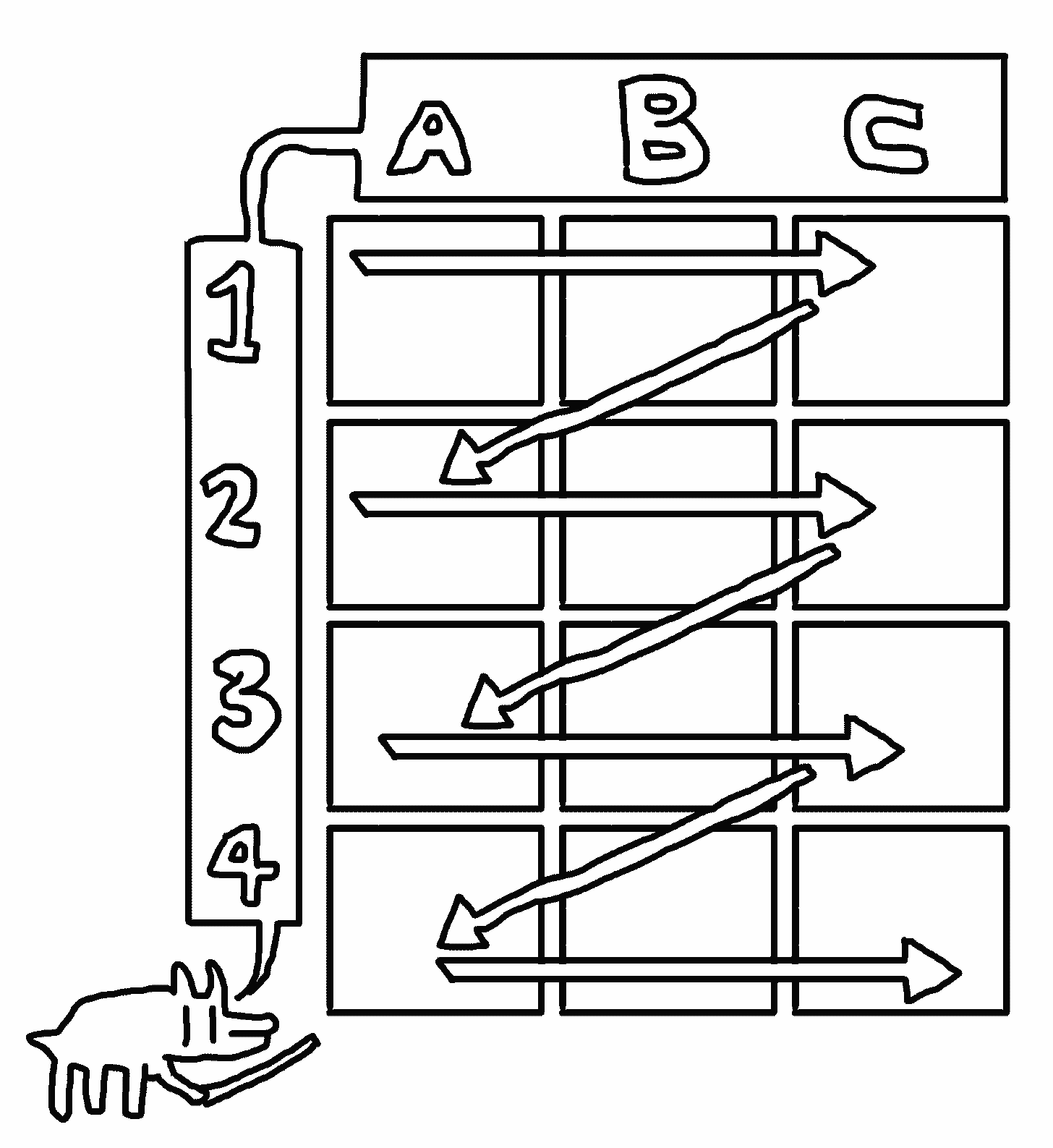

Number the tiers from 1 to 4 and label the columns A, B and C. The way the strip as a whole is intended to be read, all twelve panels in sequential order, is as follows.

Panel 1A: Promoter and Castor rush to find Popeye.

Panel 1B: Promoter and Castor ask Popeye to fight for money; Popeye agrees.

Panel 1C: Promoter and Castor turn back in the direction they came to head to the arena; Popeye walks out of frame in the opposite direction to prepare for the bout.

Panel 2A: Promoter heads into the arena to announce the fight; Castor follows with enthusiasm.

Panel 2B: Promoter stands in the ring with a packed house and hollers out the fight announcement.

Panel 2C: Closeup of ringside attendees (and full rows behind them as far as the eye can see). “We wants action!” “Give us a knockout!” “Bring ‘em on!”

Panel 3A: Castor in private tells Popeye “there are fifteen thousand people out there expecting to see a terrific battle - now for cryin’ out loud do your best!” Popeye assents.

Panel 3B: Closeup of two attendees noting that both fighters are sailors and anticipating a good fight because “sailors always put up good scraps.”

Panel 3C: Popeye standing in his corner ready to brawl; Castor tells him “when the gong sounds just step up an’ slam ‘im in the bread basket.”

Panel 4A: Popeye and the other sailor/boxer stride into the center of ring, come nose to nose and are startled.

Panel 4B: Popeye recognizes his old shipmate Joe Barnacle. Joe recognizes Popeye. They beam with happiness and shake hands.

Panel 4C: Popeye and Joe sit on the ropes with their arms around one another recounting old sailor stories. Castor, the promoter and all fifteen thousand attendees are wide-eyed and slack-jawed with shock. The one thing no one expected, including Popeye and the reader, was for Popeye to not punch someone out in the punchline panel!

You can see how this straight-through reading of the entire strip breaks down easily into tiers because that’s how one would read it anyway. Any of these tiers could pretty much work as a single daily strip in a four-day sequence but they also flow together seamlessly at a pace different from that of the dailies because Segar is stretching out and telling a twelve-panel story in one sitting.

The three panels in the first tier establish the fight scenario. The second tier gets us from the arena entrance to the ring to a view of the at-capacity and bloodthirsty crowd. The third tier takes us from Castor and Popeye on their own to out in the corner of the ring, with a panel in the middle to introduce the narrative feint that this should be an especially good fight because Popeye’s unseen opponent is also a sailor. The fourth tier has the moment of recognition, the exposition of familiarity and the punchline of camaraderie — in the one environment where he is specifically required to fight, Popeye confounds everyone’s expectations by being chummy and sentimental.

Now consider it as read in columns instead. Because each tier and the three panels that comprise it are composed so as to efficiently hustle along that section of story, you can read the panels vertically in columns and find more or less that it still works.

Panel 1A: Promoter and Castor rush to find Popeye.

Panel 2A: Promoter heads into the arena to announce the fight; Castor follows with enthusiasm.

Panel 3A: Castor in private tells Popeye “there are fifteen thousand people out there expecting to see a terrific battle - now for cryin’ out loud do your best!” Popeye assents.

Panel 4A: Popeye and the other sailor/boxer stride into the center of ring, come nose to nose and are startled.

Panel 1B: Promoter and Castor ask Popeye to fight for money; Popeye agrees.

Panel 2B: Promoter stands in the ring with a packed house and hollers out the fight announcement.

Panel 3B: Closeup of two attendees noting that both fighters are sailors and anticipating a good fight because “sailors always put up good scraps.”

Panel 4B: Popeye recognizes his old shipmate Joe Barnacle. Joe recognizes Popeye. They beam with happiness and shake hands.

Panel 1C: Promoter and Castor turn back in the direction they came to head to the arena; Popeye walks out of frame in the opposite direction to prepare for the bout.

Panel 2C: Closeup of ringside attendees (and full rows behind them as far as the eye can see). “We wants action!” “Give us a knockout!” “Bring ‘em on!”

Panel 3C: Popeye standing in his corner ready to brawl; Castor tells him “when the gong sounds just step up an’ slam ‘im in the bread basket.”

Panel 4C: Popeye and Joe sit on the ropes with their arms around one another recounting old sailor stories. Castor, the promoter and all fifteen thousand attendees are wide-eyed and slack-jawed with shock. See above: for once a Popeye punchine packs no punch. Segar has told a whole story, built up our expectations and marvelously confounded them in twelve succinct panels, every one of which is drawn with both beauty and economy.

The timeline doesn’t function the same way in both readings; this alternative way of looking at the strip is definitely more akin to reading four separate daily strips that keep jumping back in time, eventually approaching the same conclusion as when the strip is read in the traditional and expected manner. This exercise merely demonstrates the natural grooves into which a working cartoonist of Segar’s caliber will inevitably settle if he sticks to his drawing table and lets the muse come find him. Because Segar was consciously or unconsciously using the four tiers along a three-column grid to arrange the sections of this concise, parable-like Sunday strip, each column works nearly as well as each tier, and the strip as a whole if read in this unconventional way almost works as well as with a proper reading.

That’s cartoonsmanship, mateys. My goodness, that’s cartoonsmanship.