Nocturnal Commissions

Three books. Two pictures. A collection of newspaper comics. The second novel in a mediocre early trilogy by a favored writer.

Roulette

I drew early ones for this entry’s three random selections from the reading list. In fact all three were from the comics library at the art school I attended in Vermont from 2010 to 2012.

Yes, Let’s by Galen Goodwin Longstreth and Maris Wicks, read in 2011. Charming and pleasingly-illustrated rhyming children’s book about a family going on a hike, centered around the rhythmic refrain of the title.

Shortcomings by Adrian Tomine, read in 2012. I don’t remember this one well except that it collects a longer work from Tomine’s legendary comic book series Optic Nerve. Tomine is a skilled and well-regarded cartoonist who works in a realistic and true-to-life style, fictionalizing many of the quotidian failures and disappointments of everyday people suffering from pain, loneliness or disillusionment.

Safe Area Goražde by Joe Sacco, read in 2012. Sacco is a capable nonfiction cartoonist, or I guess one might more specifically call him a journalistic/historical cartoonist. I was probably reading this around the time he came to do a visiting artist lecture at said art school. A handful of us got to go out for a drink with him, which was fun; he’s a soft-spoken and intelligent fellow who makes stimulating bar conversation. He probably honed some of those skills going firsthand into conflict zones to generate material for his comics reportage; Safe Area Goražde finds him investigating life for civilians on the ground during the Bosnian War.

Sacco’s draughtsmanship and scholarly breadth of knowledge make him arguably the current best at what he does, though his editorializing has on occasion lapsed into factual errors or moralizing misrepresentations. (I don’t know or recall offhand if this is true of Safe Area Goražde in particular.)

Altogether I’ve read three of Sacco’s books. His finest accomplishment is certainly 2013’s The Great War - July 1, 1916: The First Day of The Battle of The Somme - an Illustrated Panorama, in which Sacco composed a continuous and very long illustration of what is described in the title, a drawing that pans in space across the battlefield from left to right and in time from morning until evening, published in a clever format that can be read by the turning of conventional “pages” or by the scrutiny of the one fold-out page that extends to something like twenty or thirty feet across. It’s an intertwining of a hardworking crafstman’s simultaneously crescendoing skill and ambition.

Picture Probation

For this entry I found myself revisiting two brilliant films, one fictional and one documentary, that both mine the absurdity and banality in some of the darkest themes of human experience by refracting them through the myth-making engine of the Hollywood film industry.

Mulholland Drive, directed by David Lynch, 2001. I’ve seen eight of Lynch’s films and this one is the best, and not because it’s the only one I ever saw in a movie theater. Mulholland Drive isn’t just better than Lynch’s other films; it’s also quite a bit better than most other films by anybody.

I saw this at a movie theater with my buddy in 2001 when it first came out. Turns out it doesn’t just hold up well but if anything has gotten better with age. This picture gathers you to its breast (and to the exquisite breasts of its two central performers) and carries you buoyantly along for a frightening, grotesque and deeply funny two hours twenty-six.

Mulholland Drive comprises a triptych of acts of discordantly varying lengths and tones that keep rearranging and inverting certain themes, names and characters. It’s some fashion of self-referential meta-noir where the first let’s say four fifths of the movie appear to possibly represent the world of dreams and the next section depicts the suffocating influx of images showing us what “really” happened before a screaming wreck of a coda seems to depict the dreamer spiraling into hallucinations before taking her own life.

The bulk of the movie is the dream section which appears to be a mystery story of lust, amnesia, casual violence and scummy Hollywood intrigue. An opulently stunning woman played by Laura Elena Harring seems to be someone of importance in the film industry who is violently deprived of any memory of who she is. She then accidentally connects with a naive immigrant ingenue played by Naomi Watts who determines to help her reconstruct her identity. Eventually Watts’s character realizes she’s helping Harring’s because she’s madly in love with her and they instantiate the most breathlessly sexy sex scene I’ve ever watched. Literally.

This is juxtaposed with other almost-but-not-quite-related story threads, including the tribulations of a wunderkind film auteur played by Justin Theroux whose attempt to complete a new project is being fucked with by moneyed interests who seem to have the backing of some conspiratorial and vaguely supernatural cabal who want to control the director’s artistic vision for unedifying reasons. (Lynch is plainly getting some stuff off his chest here.) The other noteworthy storylines depict a couple of squares discussing the nature of overpoweringly vivid dreams and their connection to real life (our first clue about the nature of what we’re watching in this part of the film) and an overconfident hitman who has a slapstick flair for haphazardly murdering more people than he needs to.

Harring’s and Watts’s characters eventually find their way to a strange performance art space where they are told explicitly that they are about to witness a sophisticated illusion and that it will be so convincing as to make them forget it’s an illusion and move them to tears, which all happens in short order. Since this is the point around which the transition from “dream” to “reality” kicks in, this sequence, pointedly set in a theater, appears to be the moment that comes closest to encapsulating Lynch’s thesis with Mulholland Drive, commenting upon the strangest aspect of both dreams and motion pictures: we know they are by definition illusory, but we still let them feel realer and more meaningful than our waking lives.

Shortly thereafter comes the harsh pivot to what I choose to view as the “real life” sequence, when we see that Harring’s and Watts’s characters represent memories and different aspects of a desperate, suicidal and homicidal woman, also played by Watts, who had her heart broken and career hopes smothered in the fell swoop of a toxic Hollywood love affair. This sequence appears to indicate that many of the odd happenings from what we’ve watched heretofore seem to be dreamily rearranged misrepresentations of what actually happened.

Then for the final few minutes of the film comes its most intense, violent and contracted portion, the sequence of horrifying hallucinations which in their harshness and brevity stand in stark contrast to the dream section, gesturing to the differences between a dream and a hallunication. Characters who seemed cartoonishly benign in the dream now seem vengeful and menacing and those who seemed vengeful and menacing now appear downright evil. The picture seems to arc towards the resolution of a mystery, which we get, albeit not in the way we expected. Then the hallucinations careen straight into horror and oblivion.

Mulholland Drive has a sophisticated but unpolished look, is hilarious and unsettling in equal measure, is never boring for a second and is characterized throughout by some truly inspired casting and acting in roles of all sizes. Top of this list is Watts, just into her thirties at the time and bursting into public awareness with a phenomenal central performance that demonstrates the versatility of a true thespian. She is responsible for a lot in this film and she does it with elan that makes it feel entirely natural. Without such a fine actor in the film’s most significant role, Mulholland Drive might not have worked so finely, even if everything else was as well-executed as it is. I can’t say enough good about this movie.

The Act of Killing, directed by Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn and Anonymous, 2012. This was my first time watching the directors’ cut of this picture and it is the better version.

This is a justifiably venerated documentary in which the filmmakers tracked down individual mass murderers who participated in the Indonesian killings of the mid-Sixties, settling focus primarily on gangster Anwar Congo and paramilitary leader Herman Koto, both of whom still at time of filming held positions of relative comfort and respect in Indonesian society and who in the film boast of their roles in the atrocities. Congo in particular is estimated by himself and others to have personally carried out about a thousand executions with his own hands.

Since Congo got his start as a petty criminal scalping tickets to movie theaters, and because these guys were downstream of Hollywood’s cultural influence even as their crimes were overlooked or tacitly endorsed by Western governments, the directors developed a fascinating insight which transformed The Act of Killing into something unique: they relaxed the guard of their subjects by encouraging them to create cinematic versions of their own horrific exploits, casting themselves as gangsters, cowboys and other Hollywood archetypes. (Noteworthily, for some reason that goes uncommented upon but is impossible to disregard, the brawny and thuggish Koto is frequently seen choosing to perform in drag.)

The killers state plainly how much they as young, bloodthirsty right-wing Indonesians looked up to tough guy marquee actors like Al Pacino and John Wayne, indicating that perhaps they derived some of the self-image they needed in order to be okay with their crimes from the violent characters those actors got famous portraying. A noteworthy refrain of the film from some of these aging mass murderers is the idea that a “gangster” is really at bottom just a man who lives in absolute freedom; it’s as if they needed the conception of macho toughness cultivated by Hollywood to reconcile themselves with and complete their ghastly project of fusing thuggery to politically-motivated mass rape and murder.

What’s most arresting about this project is how the process of encouraging these guys to first reflect upon and then reenact their crimes, casting themselves variously as themselves, as one another and as their victims, brings bubbling to the surface feelings of reflection and remorse that they have been repressing for decades. Congo in particular, who emerges as something like a protagonist for the documentary, is captured beginning to derive from his filmmaking exploits the seed of an insight into just how deeply horrible his actions were for the people who had to die by his hands and, when words fail him, having a physiological response in which he tries literally to vomit up years of nightmares and pent-up remorse. A disquieting and yet compulsively watchable examination on the nature of murder and guilt and on the power of filmmaking as a tool for propaganda, entertainment and self-insight.

Comics Court

I finished reading The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book.

Whomever was hoarding the other comics collection I was waiting for finally returned it, so I got my hands on The Complete Little Nemo in Slumberland Volume II: 1907-1908 by Winsor McCay, edited and with an introduction by Richard Marschall. I’m reading the second volume in lieu of a first simply because it’s the one the public library had available.

Around the time I read those books from this entry’s first section, I heard Jules Feiffer give a talk in a church in New England in which he correctly noted that McCay established himself as arguably the greatest newspaper cartoonist ever while the medium itself was still in its infancy, potentially making the game much less fun for all who have been swimming in his wake ever since. (Paraphrasing but doing it rather well, if I may say so.) I agreed with Feiffer’s assessment because I had already been nursing a modest obsession with McCay and his work for years before that, reading collections of Little Nemo in Slumberland and McCay’s lesser-known but often equally great sleep-based strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, watching a collection of McCay’s complete animations including the stunning bit of war propaganda The Sinking of the Lusitania and reading John Canemaker’s excellent coffee table biography Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. (Typing all of this out, I realize how fucking McCay-fixated I was for a few years there in the late Aughts.)

Last night when I couldn’t sleep in the wee hours I finished Marschall’s short-but-snoozy scholarly introduction. Now I’m ready to jump back into these marvelous comics and quite looking forward to it.

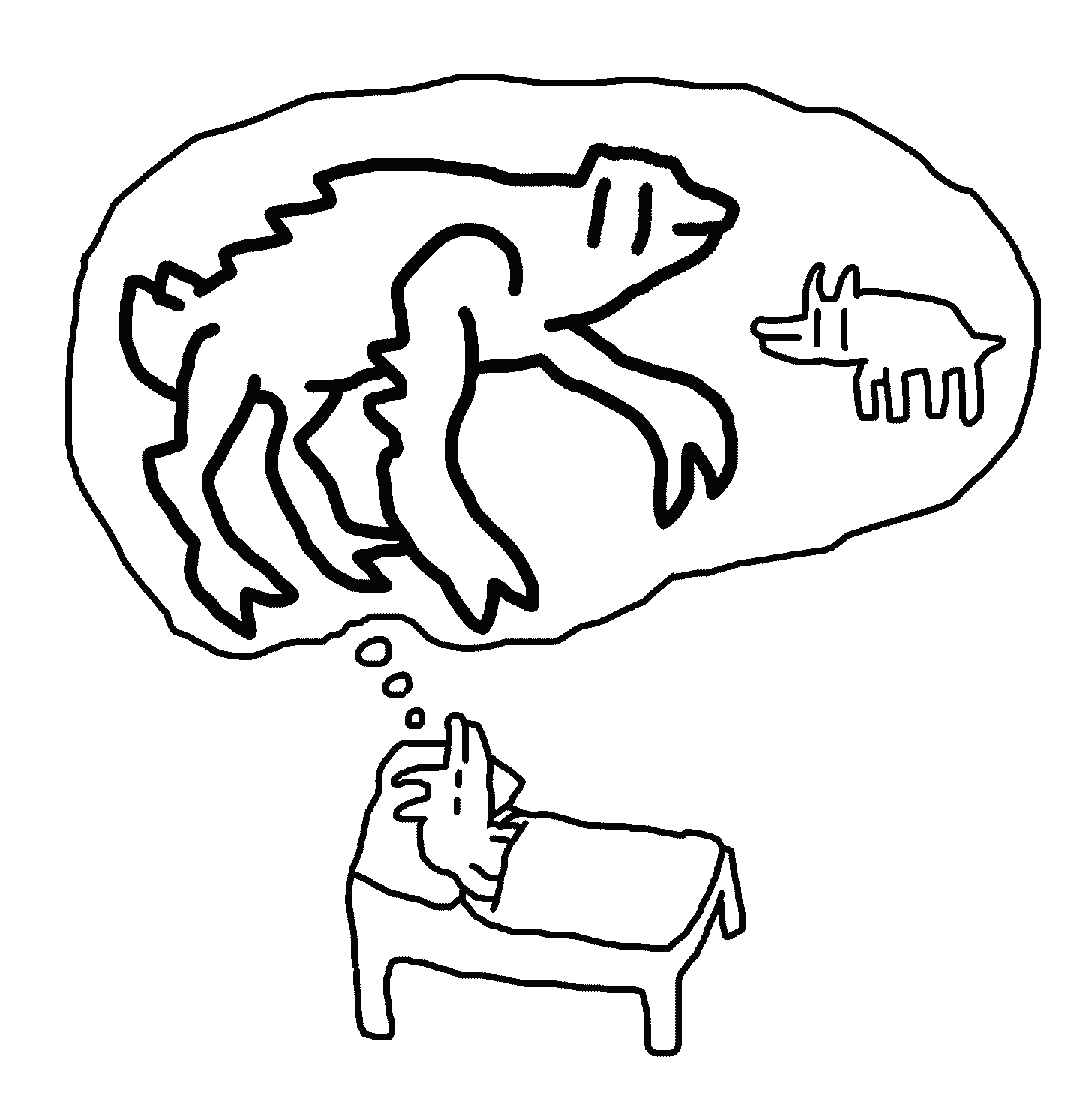

For the uninitiated — each installment of Little Nemo in Slumberland is an elaborate full-page dream sequence which culminates in the kid Nemo, in a final tiny panel that is always tucked away in the bottom right corner of the layout, waking up in bed and making some real-life comment that relates to what he was dreaming about. Meanwhile each dream continues an ongoing narrative of Nemo and his imaginary sidekicks making their way through ever-more trippy and elaborate environments and encounters in “Slumberland” in which absolutely anything can and does happen, rendered with enveloping convincingness by McCay’s masterful drawing abilities. He’s every bit as skilled as, say, Tomine or Sacco, but with the churning, unrelenting proficiency of an old-time hack journeyman combined with a much more freewheeling and inventive imagination than those neorealist cartoonists of a century later. More thoughts forthcoming as I dig into the comics proper.

Literature Litigation

I’m still reading L.A. Noir by James Ellroy. I was well into the second novel in the book, Because the Night, when the public library of Oakland from whom I got it through San Francisco’s inter-library loan decided that they wanted their copy back and that I couldn’t renew it.

I was forced to use an online retailer to track down a cheap used paperback copy, but at least now I can finish re-reading Ellroy’s trilogy of Lloyd Hopkins novels at an easygoing pace. This is handy because there is a significant jump in verbal density and plot complexity from Blood On the Moon to Because the Night. I’m almost done re-reading Because the Night and can say that in terms of style it shows much more maturity than the first Lloyd Hopkins story. It also finds Ellroy stretching muscles for denser plotting and more sprawling dramatis personae, ones he he would continue to flex much more robustly in the stellar middle works he began putting out a few years after the Hopkins books.

Because the Night finds Ellroy tinkering with the structure he established in Blood On the Moon. In the earlier book the rogue prodigy detective Hopkins and his serial killer nemesis stumble upon awareness of one another and then circle warily until only Hopkins is left standing. Because the Night carries over the setup of showing the killer’s perspective and trajectory in counterpoint with Hopkins’s investigations and personal problems, but Ellroy pushes it into new territory in the second book by establishing that the killer is already stalking Hopkins before Hopkins ever becomes misdirectedly aware of him as someone who might be able to help with the case.

Ellroy also seems to have gone in search of a way to make this killer even more of a menace than the woman-slaughtering psychopath from the first novel and found it by characterizing Dr. John Havilland as an evil cult leader masquerading behind a facade of professional respectability who doesn’t just kill but manipulates his acolytes into doing much more and more brutal killing, just to see if he can, just to see how good he really is at controlling the minds of other human beings and what he can learn about the will and freedom to do evil.

As with the first novel, Hopkins’s personal life is this fictional police detective’s cliche of a disaster zone, and once again the horndog, woman-obsessed Ellroy can’t help but interject a plot component in which killer and detective are in love with the same ravishing woman. A cheap and effective way to get some titillating sex scenes in there and to ratchet up the personal stakes for Hopkins in trying to bring Havilland down before the villain can drag the woman down with him. I can’t remember from my first reading of Because the Night if Lloyd succeeds at saving her as he did with the commensurate character in Blood On the Moon. But given the clouds darkening on the horizon of Ellroy’s imagination and his evident desire to push everything about the Hopkinsverse “beyond the beyond” (to use Havilland’s catchphrase), I’m guessing that things turn out even less well for Linda here as they did for Kathleen in Lloyd’s first outing. Give me fifty-six pages of reading and the next entry of this newsletter to find out.