Luca is the new offering from Pixar Animation Studios. As usual it’s a dazzling visual spectacle to behold, but overall its not Pixar’s best work and doesn’t benefit from comparison with its outstanding 2020 predecessor Soul. Conceptually Luca feels like it should have been one of those shorts that Pixar sticks on the beginning of their features but got dragged out and propped up to justify its length. Pixar movies always have a “Pixar does” premise; Soul was “Pixar does jazz,” The Incredibles was “Pixar does superheroes,” Cars was “Pixar does cars” and so on. But Cars notwithstanding, they usually find something substantive or profound to say about meaningful spiritual and moral issues, and Luca, which is “Pixar does merfolk,” isn’t packing anything in that department beyond platitudes about children growing up and parents letting go and bullies being bad and friendship being good and shit. It’s set in an Italian fishing village after World War II, and the studio’s designers and animators have certainly outdone themselves once again with how jaw-droppingly beautifully they’ve rendered weather, architecture, fabrics and textures, which is enough to make it worth the watch overall. Just don’t expect it, as Pixar films regularly do, to make you bawl or chortle or ponder or marvel.

Next I watched The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the 2011 English-language version directed by David Fincher, a beautiful-looking picture about two beautiful-looking people who neutralize all the squares and scumbags who get in their glossy, pouty way. This was the last Fincher movie I hadn’t seen, if it could be fairly said that I’ve “seen” his first picture Alien 3, which I sat through once when I was about twelve on a pan-and-scan VHS tape. Alien 3 was released in 1992 but I’ve thought of Fincher rather as the last of the Seventies-style auteur-types to sneak into the studio system and make successful pictures mostly without compromising his dark view of human nature and distinctive aesthetic (latex/steel/glass/wood, cool tones, elegant compositional geometry, slickly-deployed visual gimmicks). The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo revisits the fascination with serial killers that the director explored in Seven and Zodiac. It’s mid-tier Fincher, watchable but not as transcendently great as his best and most genre-confounding work in Fight Club and The Social Network. I’ve never read any of the Stieg Larsson fiction on which Fincher’s film was based or seen any of the original Swedish-language adaptations that preceded it, so I went in with little idea of what to expect in terms of content. I won’t waste ink trying to recap the dense story, key chunks of which I couldn’t quite follow, but the film is structured around two parallel character tracks, one for Rooney Mara’s eponymous girl with the eponymous tattoo and one for Daniel Craig as a journalist in need of a gig who gets more than he bargained for when he’s hired by a wealthy industrialist to solve a decades-old family mystery that may or may not be a murder case. When these characters’ discrete stories converge, they find that they complement one another well enough to crack the case and tie off dangling narrative threads. I know most northern European people are fluent in English, and it’s likely I’m simply too ignorant to appreciate that it’s more plausible than I think it is that nary a word of Swedish is spoken in this Sweden-set movie about all Swedish characters, but it preoccupies me when we’re just meant to quietly accept that people in such extremis would choose to strictly speak English for the accessibility of the American filmgoing public. Craig, as usual, performs with a smirking hint that he thinks maybe the whole movie business is just silly. Mara’s tough, clever, eccentric character defiantly endures nightmarish on-screen abuse and sports a hairstyle that grows increasingly conventional as she withstands her trials, links up with Craig’s character and becomes more well-rounded, jaded and mature. Roles are inhabited by great actors like Stellan Skarsgård, who seems happily consigned to exclusively and perpetually play creeps and deviants, and Christopher Plummer, your go-to man when casting a dashing family patriarch. A particularly sneering, methodical, violent (if morally righteous and high-toned) study in craftsmanship from a decade ago that wouldn’t get past the safteyist censors of the present.

In a breezy two hundred and thirty-two pages, Julia Galef’s 2021 book The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t makes a strong case for why any curious truth-seeker who wants “to stop self-deceiving and view the world realistically” should conduct one’s intellectual pursuits not in “soldier mindset,” where the goal is to sustain and defend beliefs or positions, but in “scout mindset,” hungry to know what is true and open to updating one’s model of reality when new information or analysis makes this possible or necessary. While acknowledging that human beings are generally wired for soldier mindset as a survival mechanism, Galef’s research and experience convincingly suggest that continually scouting out what’s true rather than what’s palatable or convenient will help individuals and groups formulate better decisions and policies. No one could emerge from the weekend it takes to get through this book worse off for giving Galef’s ideas fair consideration, but The Scout Mindset would be especially appropriate as a gift for a still-forming mind or recent graduate.

It’s been a while since I played Roulette, where I use a random-number generator to pick out three books from the complete reading list I’ve maintained since the beginning of 2010. This spin of the wheel turned up some arresting graphics and inventive design concepts.

Firecrackers! An Eye-Popping Collection of Chinese Firework Art by Warren Dotz, Jack Mingo and George Moyer, read in 2018. I stumbled on this on the shelves of the public library. The title tells you precisely what you’re getting but can’t do justice to the splendor of the kitschy, eye-gouging artwork within. I didn’t know this area of commercial art design existed but glad to have learned. This book has almost no text to even try to draw your eyes away from the images, which would be a futile endeavor anyway.

Safari Honeymoon by Jesse Jacobs, read in 2015. A 2014 graphic novel from the venerable Canadian cartoonist Jacobs, possessor of a psychedelic astral-zoological imagination that he keeps rooted in tightly-bottled stories and meticulously-composed page layouts. He designs strange characters and agoraphobic environments with a novel sense of how to get your eye from one panel to the next, using repition and symmetry to create emergent patterns in the narrative and on the page. I forget the story particulars, but this book has something to do with a couple’s confused relationship being metaphorically and manifestly constrained by the wild, otherworldly plants and animals they encounter on their safari honeymoon. Light on text and dialogue and heavy on trippy visuals and inventive design.

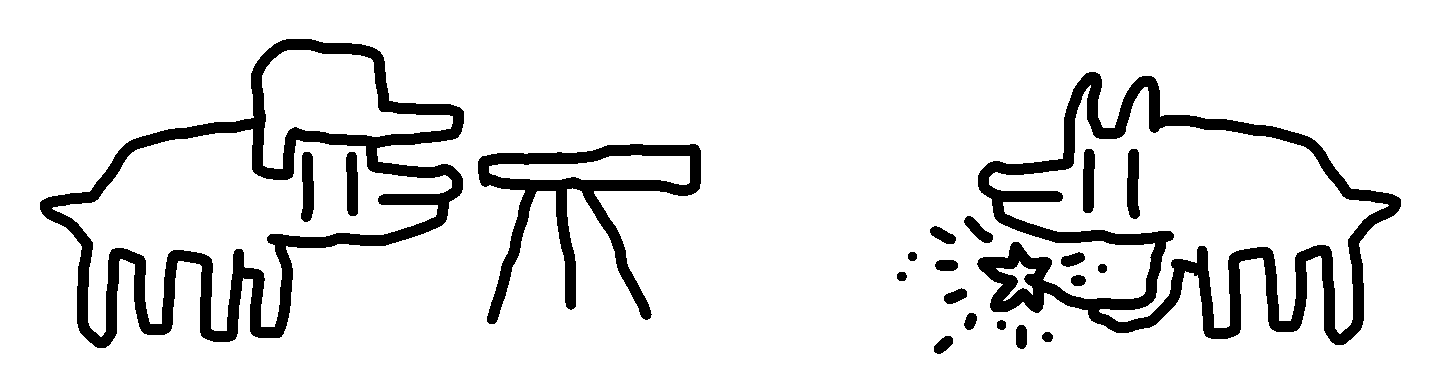

Jimbo’s Inferno by Gary Panter, read in 2014. I mentioned in a recent entry having read Crashpad, the newest in the cartoonist legend Panter’s ongoing series of large-scale hard-back coffee table comic books. While Jacobs’s career is downstream of the Cartoon Network plush-toy stoner animation culture of the Aughts, Panter has been making aggressively-drawn eschatalogical punk comics since the Seventies, often featuring the spiky-haired naif wanderer Jimbo, said by some to have been an inspiration for Bart Simpson. Jimbo’s Inferno is a “Ridiculous Mis-Recounting Of Dante Alighieri’s Immortal Inferno” which finds Jimbo exploring a tacky, dystopian “Vast Gloomrock Mallscape” called Focky Bocky, inhabited by garishly cartoony robots, critters and monsters. The books of Jacobs and Panter, like those of other cartoonists to which I’m often drawn, are dense and sprawling, more easily respected than enjoyed and demanding of regular revisitation.